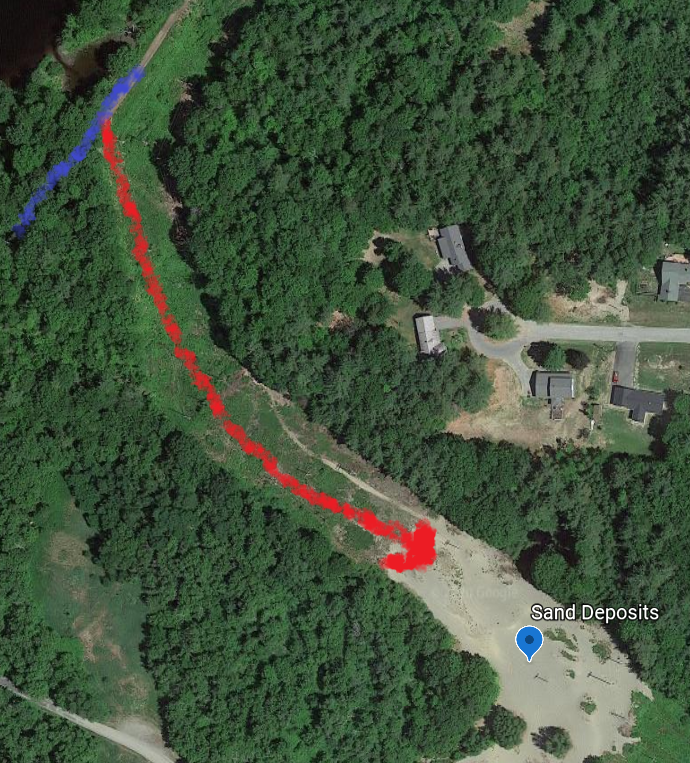

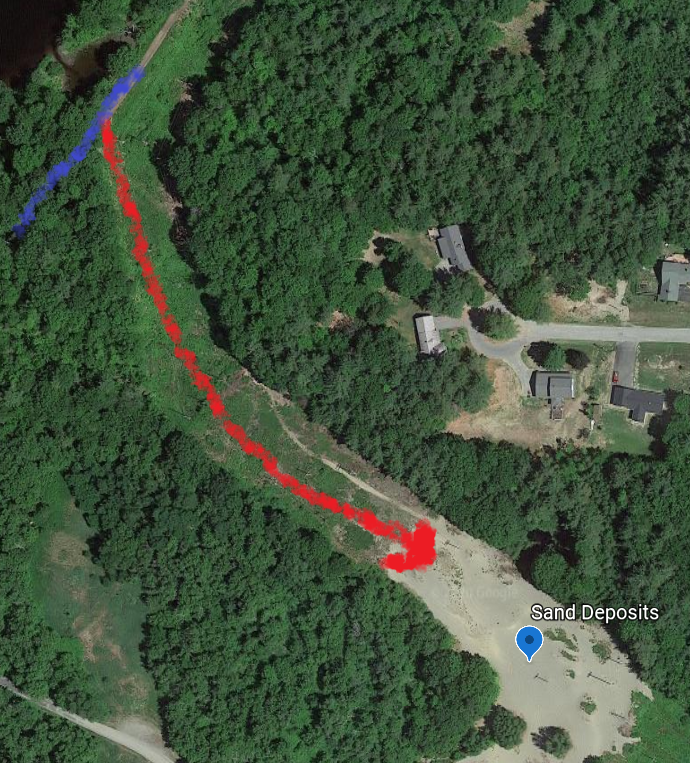

A Desert in Winslow?

To Locate the second feature, you will wander uphill within easy sight of the trail. Follow the Power line up the slope. At the top you will find a small “desert” , another deposit of the Presumpscot formation. It’s an interesting area to explore. If you are a tracking enthusiast you can also find lots of animal tracks and signs. If you follow the sandy area to the right it will bring you back to the access road uphill from the trail parking lot.

Incidentally you will likely find several small streams on your way up the slope, likely originating from the perched water table!

More About The Presumpscot Formation

From MGS

https://digitalmaine.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1334&context=mgs_publications

During the end of the last Ice Age, when the great ice sheet was melting, its margin had reached the present coast of Maine about 16,000 years ago. The mass of ice had caused the earth’s crust to bend downward, and as the ice margin retreated, the ocean flooded the downwarped areas when they became ice free. Into this glacial-marine environment, glacial streams deposited great quantities of sediment ranging in size from coarse to fine materials. The fine particles such as fine sand, silt, and clay were deposited as a blanket of mud away from and over the coarser materials. This glacial-marine mud is ubiquitous in the region that was flooded, and is called the Presumpscot Formation, named for exposures along the Presumpscot River in Portland (G

This unit is well known to people who live along the coast or in inland lowlying areas. Anyone who has had to dig through it has found it can be a sticky mess! Water-well drillers have reported thicknesses of the mud as great as 200 feet. More commonly it is a veneer or drape over bedrock or glacial sediments of varying thickness (Figur

It contains the ground-up fragments of minerals that make up the bedrock of Maine, such as quartz, feldspar, and mica, but in very tiny pieces.

Economically, the glacial-marine mud was used for making bricks for many years, its legacy noted by names such as Brickyard Hill and Brickyard Cove. It was undoubtedly used by Native Americans for making their clay pottery, and by early Maine settlers and later industry for ceramic products including the earthenware known as Maine Redware. It is used today by some local potters and artisans for decorative pieces, many of whom are listed on-line. Today, its most common use is as an impermeable fill to cap landfills or other hazardous-waste sites.

The Presumpscot Formation is generally called “blue clay” by the public, but its color is usually gray (Figures 4 – 6), and its composition is more often dominated by silt-sized particles rather than clay-sized ones.

Maine’s bedrock foundation is covered in many places by surficial earth materials such as sand, gravel, silt, and clay. These sediments were transported and deposited by glacial ice, water, and wind. Many of them formed during the “Ice Age”, which occurred between about two million and ten thousand years ago. Others were laid down more recently in stream, shoreline, and wetland environments. The colors on the map represent various kinds of surficial sediments. We will see examples of the most common types in the following photos

Surficial geology is important to Maine’s citizens for economic and environmental reasons. Most of the sand and gravel used in construction, concrete, and sanding roads in winter was originally deposited by streams from melting glacial ice. Gravel pits are often located in these glacial deposits. The deeper parts of many sand and gravel deposits contain large quantities of water and are classified as aquifers. Yields from some aquifers are so large that they can supply water to municipal wells and the bottled water industry.

Information about the type and thickness of surficial sediments is used in planning highway and building projects such as the new bridge across the Kennebec River in Augusta (shown here in an early stage of construction). Geologic maps and test borings help engineers to determine the depth to bedrock, foundation requirements, and possible stability problems.